Executive Summary

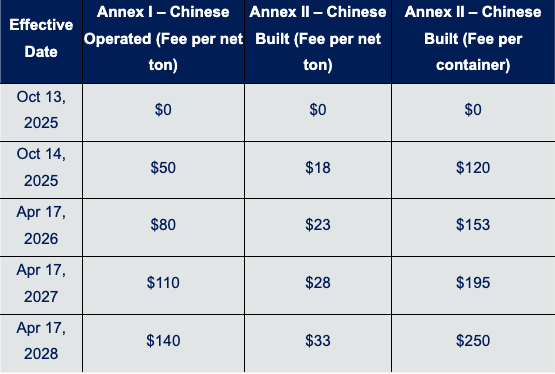

Effective October 14 2025, Section 301 maritime fees introduce two cost schedules for vessels tied to China:

- Annex I applies to Chinese•operated ships at $50 / net ton (NT) in 2025, increasing to $140 / NT by April 17 2028

- Annex II covers any Chinese•built ship (regardless of operator) at the higher of $18 / NT or $120 per container in 2025, climbing to $33 / NT or $250 per container by 2028.

- Each vessel will be charged up to five times annually, once per U.S. rotation, meaning exposure depends on service frequency and fleet composition.

For importers, the added cost per box may vary widely. On large Chinese‑operated megaships, the tariff could translate to roughly $550–1,600 per container over the 2025–28 ramp‑up. Carriers using Chinese‑built vessels might see $175–400 per box, depending on whether the NT‑based or per‑container formula dominates. Because carriers have publicly stated their intent to pass these fees through, importers could see ocean‑freight bills to rise by 10% to over 40% per box on services exposed to Annex I or Annex II vessels as the program escalates through 2028.

In April 2025, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced a trade action under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 targeting maritime transport services linked to China. This action introduces new fees on ocean vessels as a countermeasure to certain Chinese policies, with the goal of pressuring China and bolstering the U.S. maritime and shipbuilding industry. These fees specifically target two categories of shipping operations:

- Chinese vessel operators or owners (Annex I) – Ocean carriers that are Chinese state-run or otherwise Chinese-owned.

- Chinese-built vessels (Annex II) – Ships that were constructed in shipyards in the People’s Republic of China, regardless of the operator’s nationality.

While these fees will be assessed to the ocean carriers, the carriers have stated that they will endeavor to pass these fees on to their customers. For small to mid-sized U.S. importers, the result is essentially a “transport tariff” on using Chinese-operated carriers or Chinese-built vessels. These fees will add costs to container shipments over the next few years, escalating through 2028. This whitepaper-style brief explains the fee structures (Annex I and Annex II of the USTR action), how they phase in, what they could mean in dollars-per-container, and strategies for shippers to adapt.

New Fee Structure Overview (Annex I & Annex II)

Under the Section 301 action, any given vessel entering U.S. ports will be subject to either Annex I or Annex II fees (or neither), depending on its ownership and build (these are not cumulative. In other words, a ship operated by a Chinese entity triggers Annex I (even if it’s Chinese-built), while a non-Chinese-operated ship that was built in China triggers Annex II (unless an exemption applies). Only one fee applies per voyage, assessed on the vessel’s first U.S. port of call in a given trip (covering all subsequent stops on that route). The fee is charged at most once per rotation (string of U.S. port calls) to prevent double-charging a single voyage.

(Table 1: Section 301 Maritime Fee Schedule, Annex I and II – 2025 to 2028)

As shown above, the cost impact deepens each year through 2028. What starts as a moderate fee in late 2025 can more than double by 2027 and reach a significant expense by 2028. Importers should use this timeline for budget forecasting – for example, a lane that costs an extra $200/FEU in 2026 might be $500+ by 2028 if reliant on Chinese-built or operated ships. Carriers, for their part, have a clear schedule to plan fleet deployments or surcharge.

Now, let’s examine each fee category and its structure in more detail:

Fees on Chinese-Operated Vessels (Annex I)

Annex I imposes a tonnage-based fee on any vessel operated or owned by a Chinese entity (including Chinese state-owned carriers). The fee is calculated per the ship’s net tonnage (NT) – a measure of the vessel’s internal volume/carrying capacity. Key points about this fee:

- Timeline: Effective October 14, 2025, the fee is $50/NT; on April 17, 2026 it rises to $80/NT; on April 17, 2027 to $110/NT; and on April 17, 2028 to $140/NT. (It remains at $0 during the initial 180-day window.)

- Application: The fee is assessed per vessel voyage (not per port call). If a Chinese-operated ship makes multiple U.S. port calls in one voyage, it incurs the fee once for that voyage. However, to prevent excessive charges on frequently-returning ships, a single vessel will be charged at most five times per year under Annex I.

In practical terms, Annex I primarily targets major Chinese shipping lines (for example, COSCO and OOCL owned vessels, etc.). These carriers will face a substantial new cost on each U.S. voyage, based on their ships’ size. As we’ll explore, this can translate to millions of dollars per voyage for the largest megaships – costs that will ultimately be passed on to the shippers utilizing those services.

Fees on Chinese-Built Vessels (Annex II)

Annex II imposes a fee on vessel operators using Chinese-built ships, even if the operator itself isn’t Chinese. This is applied on a non-discriminatory basis – any carrier (American or foreign) that deploys a ship constructed in China will pay the fee. The structure of this fee is a bit more complex, as it uses the higher of two calculations:

- A net tonnage–based fee, similar to Annex I (dollars per net ton of the vessel), or

- A per-container fee, based on the number of containers discharged in U.S. ports

The vessel operator must calculate both and pay whichever is greater. This ensures that whether a ship is partially loaded or fully loaded, it pays a fee either way. Key details of Annex II:

- Net tonnage fee: $18/NT starting Oct 14, 2025, rising to $23/NT on Apr 17, 2026, $28/NT on Apr 17, 2027, and $33 per net ton by April 17, 2028.

- Per-container fee: $120 per container (FEU/TEU*) starting Oct 14, 2025, rising to $153 on Apr 17, 2026, $195 on Apr 17, 2027, and $250 per container by April 17, 2028. (*The fee applies per container unit, presumably per loaded container regardless of size. A 40-foot container would count as one unit for fee purposes the same as a 20-foot container.)

- “Whichever is higher” rule: For each U.S. entry, the $/NT calculation and $/container calculation are compared, and the operator pays the higher dollar amount. This means a lower utilized vessel still pays based on its tonnage, while a fully-loaded vessels pays based on containers – with the target to maximize the fee in both scenarios.

- Application and cap: Similar to Annex I, the fee is assessed per voyage (per string of U.S. port calls) and is capped at five occurrences per year per vessel.

- Exemptions: Recognizing that a broad fee on Chinese-built ships could catch certain critical or niche vessels, the USTR carved out specific exemptions. Vessels not subject to Annex II fees include:

- U.S.-flag vessels enrolled in certain U.S. Maritime Administration programs (e.g. Maritime Security Program, Tanker Security Program, Voluntary Intermodal Sealift Agreement).

- Vessels arriving empty or in ballast.

- Smaller vessels below certain size or capacity thresholds (the exact threshold is defined in the annex – intended to spare very small ships).

- Vessels engaged in short sea shipping – defined as voyages under 2,000 nautical miles from certain U.S. ports (e.g. regional feeder services, Great Lakes, Caribbean routes, South America/Latin America).

- Vessels of certain U.S.-owned companies (even if built in China).

- Certain specialized export vessels, likely meaning ships dedicated to specific U.S. export trades (these could be things like LNG tankers or other specialized carriers not in the mainstream liner service).

- Fee remission incentive: To encourage a shift toward U.S. shipbuilding, there is a unique incentive in Annex II – if a vessel operator orders a new U.S.-built ship of equivalent size and takes delivery, they can get a temporary fee waiver (remission) for up to 3 years on an equivalent Chinese-built vessel. In short, a carrier that invests in U.S.-built tonnage can avoid the fees on one of their Chinese-built ships during the construction/delivery period of the new ship. This is a strategic long-term option for carriers to eventually eliminate these fees, though it won’t have immediate effects for most importers.

Together, Annex I and Annex II create a two-pronged fee regime aimed at Chinese maritime influence: one targets Chinese shipping companies, and the other discourages the use of Chinese-made ships by any company. The net-tonnage versus per-container basis in Annex II is a critical distinction we’ll clarify next, as it affects how and when each fee kicks in.

Net Tonnage vs. Per-Container Fees: When Does Each Apply?

For Chinese-operated vessels (Annex I), the fee is only based on net tonnage of the ship. There is no consideration of container count – even an empty Chinese-operated ship would incur the tonnage-based fee (except during the initial free period). Shippers using a Chinese carrier cannot avoid the fee by shipping fewer containers; the fee is tied to the vessel’s size, not the cargo load.

For Chinese-built vessels (Annex II) operated by non-Chinese carriers, the fee calculation is dual: the ship’s operator must calculate the fee both ways and pay whichever amount is higher. Here’s how to understand the dynamics:

- Net tonnage fee (Annex II): This acts like a minimum base charge related to the ship’s capacity. Net tonnage (NT) is a measure of the ship’s volume/capacity. Larger ships have higher NT. This fee is fixed per ship per voyage (e.g. a 50,000 NT vessel at $18/NT = $900,000). It does not depend on how many containers are actually on board – it’s essentially a charge for the capacity the ship brings into a U.S. port.

- Per-container fee: This is a usage-based charge tied directly to how many containers the vessel actually discharges in U.S. ports. For example, at $120 per container, if 5,000 containers are unloaded, that’s $600,000 fee; at the $250 rate in 2028, the same 5,000 containers would incur $1.25 million. This fee scales with cargo volume.

The higher of the two ensures that a carrier can’t game the system by, say, running a nearly empty Chinese-built ship to pay a tiny per-container fee – they’d still pay the tonnage-based minimum. Conversely, if they fill every slot on a large Chinese-built vessel, the per-container calculation likely exceeds the tonnage fee, so they pay that higher amount. In essence, the fee will always at least equal the tonnage-base, and in high-volume voyages it will exceed it.

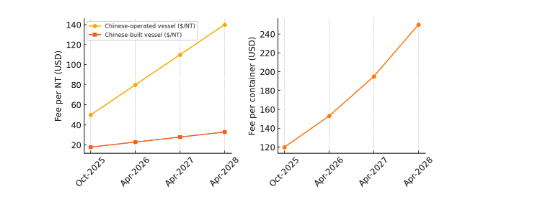

Fee escalation timeline for the new Section 301 maritime fees. The left panel shows the per-net-ton fee increases for Chinese-operated vessels (yellow line) versus Chinese-built vessels (orange line). The right panel shows the per-container fee for Chinese-built vessels (applicable when it exceeds the tonnage-based fee). From late 2025 to 2028, the fees ramp up steeply: e.g. Chinese-operated ships go from $50 to $140 per NT, while Chinese-built ships’ container fee rises from $120 to $250 per box.

As shown above, the cost impact will significantly increase each year through 2028. Importers need to factor in not just the immediate extra cost, but the year-over-year escalations when planning freight budgets and long-term contracts.

Example Scenarios: Cost Impact on Shippers

To put these fees into perspective, let’s walk through a couple of example scenarios and estimate the additional costs:

Scenario 1: Chinese-Operated Vessel (Annex I)

Imagine a large container vessel (Chinese-operated) calling at U.S. ports on the west coast:

- Vessel: 14,000 TEU capacity (e.g. ~80,000 NT net tonnage).

- U.S. Calls: 6 full rotations per year (roughly on US call every two months based on roundtrip transit time from Asia). Under Annex I, only 5 of those incurs fees due to the cap of five per year; one voyage would effectively be free of the fee.

- Cargo Volume: On each U.S. call, it carries ~7,000 containers for U.S. importers.

Initial impact (late 2025): At the $50/NT rate, each call costs $50 × 80,000 = $4 million in fees. With ~7,000 containers, that works out to about $571 per container in added cost. If the ship calls 5 times in a year with the fee, that’s $20 million annually in new fees for that one vessel. Those costs will be spread across all importers using that ship (likely as a surcharge). For an importer moving 100 containers on that voyage, that’s roughly an extra $57,000 on that shipment’s cost.

Full impact (by 2028): At $140/NT, each call would incur $140 × 80,000 = $11.2 million in fees – roughly $1,600 per container if 7,000 boxes are aboard. Five such voyages in a year would tally $56 million in fees on this one ship. Even if carriers optimize loading, the per-container fee equivalent is on the order of hundreds to over a thousand dollars. In practice, a carrier might try to maximize utilization to dilute the fee per box (or conversely might deploy a smaller ship – but that has its own capacity trade-offs). Either way, importers using a Chinese carrier could see somewhere from $500 to $1,500+ added per container by the late stages of this policy, depending on vessel size and load factor.

Scenario 2: Non-Chinese Carrier with Chinese-Built Ship (Annex II)

Now consider a global carrier (not Chinese-owned) – for instance, a European or Southeast Asian shipping line – that happens to use some vessels built in China:

- Vessel: 10,000 TEU capacity (~ 60,000 NT). Let’s say this ship was built at a Chinese shipyard, so Annex II applies.

- U.S. Calls: 4 rotations per year (quarterly service). All would be subject to the fee (within the 5/year cap).

- Cargo Volume: ~5,000 containers delivered to U.S. per voyage (typical for a 10k TEU ship, assuming many 40′ containers).

Late 2025: At initial rates $18/NT vs $120/container, the higher fee would likely be the tonnage-based: $18 × 60,000 = $1.08 million per voyage, versus $120 × 5,000 = $600,000. So, the ship pays $1.08M (tonnage method). That’s roughly $216 per container in this scenario. For four voyages, total yearly fees = ~$4.3M.

By 2028: Rates $33/NT vs $250/cont. Now tonnage fee = $33 × 60,000 = $1.98 million; container fee = $250 × 5,000 = $1.25 million. Here the tonnage fee is still higher, so the ship pays ~$1.98M (about $396 per container). If the ship had more cargo (say 6,500 containers), the container-based fee ($1.625M) would exceed tonnage ($1.98M vs $1.625M – actually in this case tonnage still higher; if 8,000 containers, container fee $2M beats tonnage $1.98M). In any case, we’re looking at on the order of $250–$400+ per container in added cost by 2028. Four voyages would rack up ~$7.9M annually in fees for this vessel.

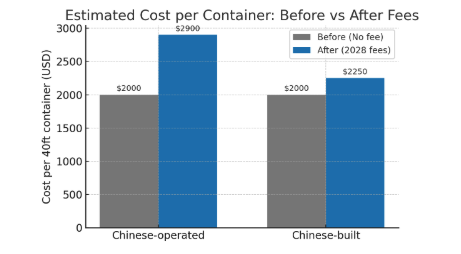

Even for a mid-sized vessel, Annex II can add a few hundred dollars per imported container. Keep in mind this is per container cost on top of existing ocean freight. If pre-fee freight was, say, $2,000 per box, a $300 fee represents a 15% surge in the freight cost – a substantial increase in landed cost for importers.

Now imagine a large transpacific service where a carrier operates 10 such vessels in a loop – the costs multiply quickly. Carriers will almost certainly seek to recover these fees from customers. They may implement a “Section 301 surcharge” or bake it into general rate increases. Either way, importers will pay more unless they can find ways to avoid the fee exposure.

Background: Section 301 Maritime Fee Actions in 2025

In April 2025, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced a trade action under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 targeting maritime transport services linked to China. This action introduces new fees on ocean vessels as a countermeasure to certain Chinese policies, with the goal of pressuring China and bolstering the U.S. maritime and shipbuilding industry. These fees specifically target two categories of shipping operations:

- Chinese vessel operators or owners (Annex I) – Ocean carriers that are Chinese state-run or otherwise Chinese-owned.

- Chinese-built vessels (Annex II) – Ships that were constructed in shipyards in the People’s Republic of China, regardless of the operator’s nationality.

While these fees will be assessed to the ocean carriers, the carriers have stated that they will endeavor to pass these fees on to their customers. For small to mid-sized U.S. importers, the result is essentially a “transport tariff” on using Chinese-operated carriers or Chinese-built vessels. These fees will add costs to container shipments over the next few years, escalating through 2028. This whitepaper-style brief explains the fee structures (Annex I and Annex II of the USTR action), how they phase in, what they could mean in dollars-per-container, and strategies for shippers to adapt.

New Fee Structure Overview (Annex I & Annex II)

Under the Section 301 action, any given vessel entering U.S. ports will be subject to either Annex I or Annex II fees (or neither), depending on its ownership and build (these are not cumulative. In other words, a ship operated by a Chinese entity triggers Annex I (even if it’s Chinese-built), while a non-Chinese-operated ship that was built in China triggers Annex II (unless an exemption applies). Only one fee applies per voyage, assessed on the vessel’s first U.S. port of call in a given trip (covering all subsequent stops on that route). The fee is charged at most once per rotation (string of U.S. port calls) to prevent double-charging a single voyage.

(Table 1: Section 301 Maritime Fee Schedule, Annex I and II – 2025 to 2028)

Estimated per-container shipping cost before vs. after the new fees in a hypothetical example. The gray bars show a baseline cost of $2,000 per 40′ container (approximate pre-fee ocean freight). The blue bars show the cost after full fees in 2028: for a Chinese-operated vessel scenario, roughly $2,900 per container (reflecting an ~$900 fee add-on), and for a Chinese-built vessel scenario, about $2,250 per container (reflecting a ~$250 fee). These estimates assume high capacity utilization and illustrate how the fees could boost shipping costs by ~12–45% depending on the situation.

As the figure above suggests, total landed costs for imports from Asia will rise as these fees are implemented. Importers will face higher ocean freight bills, which translate into higher costs per unit of goods imported. Businesses importing low-margin products (like basic commodities or retail goods with slim profit margins) are particularly vulnerable – an extra few hundred dollars per container can erode profitability or force price increases to end customers. Even importers of higher-value goods will need to account for these added logistics costs in their pricing models.

How Carriers Might Respond

Carriers are not passive players in this scenario – they will look for ways to mitigate the impact on their operations and profitability (even as they pass costs to shippers, they have strategic decisions to make). We may see several possible carrier responses in reaction to the Section 301 maritime fees:

- Fleet Deployment Adjustments: Large shipping lines operate global fleets with vessels of various origins. We expect carriers to redeploy vessels to minimize fee exposure. For example, a carrier might assign its Chinese-built ships to routes that do not call the U.S., such as Asia–Europe routes, and bring more Korean-built or Japanese-built ships to the trans-Pacific trade. Similarly, Chinese state-run carriers (subject to Annex I) might try to swap vessels within alliances so that a partner’s non-Chinese-operated ship handles U.S. port calls on certain loops. Alliance networks (like Gemini Cooperation, Ocean Alliance, Premier Alliance, etc.) provide some flexibility – e.g., if one member’s ship would incur higher fees, they might use another member’s ship on that service, if available, to reduce costs for all alliance members. However, such adjustments have limits, as many carriers have numerous Chinese-built ships in their fleet mix after years of cost-effective ordering from Chinese yards.

- Route Diversion (Canada/Mexico Transshipment): In an extreme case, carriers (or even large shippers) might consider routing cargo through nearby foreign ports to avoid U.S. entry fees. For example, an Asia ship could go to Vancouver or Prince Rupert in Canada, or Ensenada or Lazaro Cardenas in Mexico, and containers destined for the U.S. could then move by rail or short-sea feeder into the U.S. Since the main voyage never “enters” a U.S. port, the Section 301 fee wouldn’t apply. However, this workaround adds complexity, time, and cost (and was explicitly flagged as a potential circumvention in the public comments. U.S. regulators will be watching for such patterns, but ultimately, they cannot impose fees on vessels that don’t call U.S. ports). We may see a modest shift to Canadian and Mexican gateways if the economics turn out favorably (for instance, if the fee per container exceeds the extra cost of transshipping through those routes). Shippers near the U.S. northern border or with flexible routing might explore this, although capacity at those alternate ports and rail links could be a limiting factor.

- Increased Use of Exempt or U.S.-built Tonnage: Another response, though limited, is for carriers to make use of any exempt vessels or seek waivers by investing in U.S. ships. A few carriers (especially those involved in U.S. government programs or Jones Act trade) have U.S.-flag or U.S.-built vessels. For example, Matson, an American carrier, operates some U.S.-built ships on the Pacific trade; these would likely be exempt from Annex II (and Matson is not Chinese-operated, so Annex I doesn’t apply). We might see niche carriers like Matson, or U.S.-flag vessels in the Maritime Security Program, become more attractive for certain shippers despite typically higher base costs, since they won’t incur the Section 301 fees. Over the longer term, carriers could consider ordering new ships from U.S. shipyards (expensive and not done in decades for large container ships) to take advantage of the fee remission incentive. While this is a long shot in the near term, the policy does aim to shift behavior over time – if a few U.S.-built container ships enter service in the late 2020s or 2030s, they would avoid these fees and perhaps get priority from cost-sensitive shippers.

- Passing Costs to Shippers: Importantly, nearly all carriers will pass these fees through to shippers one way or another. Whether as a line-item surcharge or baked into freight rates, carriers are not expected to absorb the fees (one reason the USTR targeted vessel owners/operators is the assumption they would pass costs, thereby putting pressure on Chinese shipbuilders by reducing demand. Shippers should be prepared to see new surcharges in their freight invoices. For instance, carriers might introduce a “Section 301 Vessel Fee” surcharge per container for cargo routed on affected vessels. Carriers with diverse fleets might create rate divisions – e.g. a service guaranteed to use non-Chinese-built ships might command a slightly higher base rate (if capacity is constrained), whereas services with Chinese-built ships will have the surcharge.

In summary, carriers will strategize to minimize how often and where they incur these fees, but they will also ensure they recover the costs from customers. We may see some shifts in network design (especially around port choices and vessel assignments), but the fundamental impacts – higher costs that will be passed on – remain.

For shippers, this carrier chess game means you’ll want to stay informed about which services are likely to incur fees and how carriers plan to structure any surcharges. In the next section, we’ll outline what U.S. importers can do to mitigate the impact.

Strategies for U.S. Importers to Mitigate the Impact

Facing the reality of these new fees, U.S. importers (shippers) should take proactive steps to manage their supply chain costs. Here are several strategies and recommendations:

- Negotiate and Plan Early: If you negotiate annual ocean freight contracts (often in the spring for Trans-Pacific eastbound), make sure to address Section 301 fees in your contracts. Push for clarity on whether the carrier’s rates include the fees or if they will be added as surcharges. Where possible, try to lock in rates before fees escalate – for example, a contract starting mid-2025 might secure a fixed rate before the October fee kicks in. Also consider shorter contract durations or re-opener clauses that allow renegotiation as the fees increase each year.

- Choose Carrier and Service Wisely: Not all services will be equally affected. Work with your freight forwarder or carrier representative to identify routes that avoid Chinese-operated or Chinese-built vessels. For instance, some carriers might publicize that a certain service loop is “Section 301-neutral” (using only non-Chinese-built tonnage). If a particular alliance’s loop is mostly operated by a Chinese carrier, another alliance’s similar loop might not be – opting for the latter could save you fees. In essence, shop around based on the vessels deployed. It may not always be transparent which ships will be used months in advance, but historical data on a service can indicate the likely vessel class and flag.

- Diversify Port Gateways: Consider routing cargo through ports or lanes that could avoid or reduce fee exposure. For example, West Coast vs. East Coast routing – if one involves a carrier using a Chinese-built fleet and another uses European-built ships, the latter route might become cost-competitive even if it was longer or more expensive before. Additionally, if you have distribution centers near Canada or Mexico, you could experiment with Canadian or Mexican port entries (as mentioned earlier) to bypass direct U.S. entry fees. Be cautious: this only makes sense if the all-in cost (including secondary transport to the U.S.) is lower than paying the fees. But with fees hitting $250/box, a cross-border rail from Canada might indeed be cheaper in some cases.

- Consolidate Shipments (Where Feasible): Because the fee is per vessel entry (not per container directly, in Annex I) and capped annually per vessel, there’s a slight advantage to moving the same volume in fewer, larger shipments rather than many small ones. If you can adjust schedules to maximize container utilization you’ll at least reduce the number of times your cargo might be on a fee-incurring voyage. This isn’t always practical, but aligning your ordering to maximize container utilization and minimize frequency could marginally reduce exposure.

- Explore Alternative Carriers (Niche or U.S.-flag): As noted, carriers like Matson or APL (which operates some U.S.-flag ships in the Maritime Security Program) might become attractive for certain lanes. Matson’s expedited service from China to Long Beach, for example, uses U.S.-crewed ships and could be exempt from the Chinese-built fee if those ships were U.S-built or fall under an exemption. These services often charge a premium for speed and U.S.-flag operation, but if other carriers are adding huge fees, the gap may narrow. Engaging with U.S.-flag carriers or niche services could provide a stable option with no Section 301 surcharges, if it fits your needs for critical or time-sensitive cargo.

- Monitor Surcharges and Look for Transparency: Keep a close eye on carrier announcements in late 2025 and beyond. When a carrier implements a Section 301 surcharge, scrutinize the level and mechanism. Some might over-collect (e.g. charging every container $300 even if the effective cost might be $200). If you’re a large BCO (Beneficial Cargo Owner), demand transparency – ask carriers to provide justification of any surcharge amounts relative to the actual fees they incur. While you likely can’t avoid paying it, you might negotiate it down or choose a competitor if one is handling it more fairly.

- Adjust Supply Chain Timing: If you have flexibility, import a bit more before the fees kick in or before each hike. For example, pulling some Spring 2026 shipments into late Summer 2025 (pre-October) could dodge the first fee increment. Similarly, plan critical inventory builds before the annual April increases if possible. This is a form of freight cost hedging – of course, it must be balanced against inventory holding costs and other factors, but timing shipments around these known fee milestones could save money.

- Engage in Advocacy: Through industry associations or coalitions, voice your concerns to regulators. While the Section 301 action is already decided, future adjustments or mitigation (or the eventual removal of fees if China changes its practices) could be influenced by industry feedback. Ensure your industry’s needs (e.g. if you rely on importing goods that are low margin) are known. There may be efforts to add further exemptions or to channel fee revenues into programs that support shippers – staying involved gives you a better chance to shape outcomes or at least be ahead of changes.

- Partner with Logistics Experts: Finally, this is a complex new cost layer. We at Bluspark are closely monitoring these developments and helping importers craft strategies to cope. Whether it’s analyzing your carrier mix for fee exposure, finding alternate routing options, or negotiating contracts that account for the fees, our team can provide tailored guidance. Don’t hesitate to reach out for a consultation on how to optimize your shipping plans under the new rules.

Be Prepared – and Let Bluspark Help Steer the Way

The new Section 301 maritime fees represent a significant change for anyone importing containerized cargo into the United States. They effectively act as a “transport tariff” on using Chinese carriers or Chinese-built ships, and they will drive up costs for many shippers over the next few years. Total landed costs from Asia are set to rise – not because of the goods themselves, but because of the ships that carry them. Importers need to adapt quickly by understanding the fee structure, anticipating carrier behaviors, and adjusting their logistics strategies accordingly.

On the positive side, forewarned is forearmed. We now have a clear timetable and structure for the fees, allowing shippers to plan ahead rather than be caught off-guard. By taking steps such as diversifying carriers, rethinking routes, and negotiating smartly, U.S. importers can mitigate some of the impact. It may also be a catalyst to explore new logistics solutions or modernize parts of your supply chain that were on autopilot.

At Bluspark, our mission is to guide shippers through challenges exactly like this. Our logistics professionals can help you analyze cost scenarios, find creative routing alternatives, and work with carriers to manage these fees. We can simulate how the fees will affect your specific lanes and product economics, and then design a plan to keep your supply chain both resilient and cost-effective.

Despite the headwinds of higher fees, with the right approach you can continue to import competitively and reliably. Now is the time to review your strategies – and Bluspark is here to assist every step of the way.

If you have questions about how the Section 301 maritime fees will affect your business, or if you need help developing a mitigation plan, contact Bluspark today.

Let’s navigate these changes together and keep your cargo flowing smoothly.

Note: As of September 11, 2025, there are no new updates regarding the U.S. tariff regulations. The next updated is expected the week of September 15, 2025, with an implementation date of October 16, 2025. Proactive planning is crucial. Develop your strategy for navigating these changes and minimizing risk with Bluspark Global before the next tariff updates go into effect.

Sources:

- USTR Federal Register Notice, Section 301 Maritime Transport Services Action

- FreightWaves, “US plans phased approach to port fees for Chinese ships” (US plans phased approach to port fees for Chinese ships – FreightWaves) (US plans phased approach to port fees for Chinese ships – FreightWaves)

- Reuters, “United States eases port fees on China-built ships after industry backlash” (United States eases port fees on China-built ships after industry backlash | Reuters) (United States eases port fees on China-built ships after industry backlash | Reuters)

- Winston & Strawn briefing, “United States Imposes Substantial Fees on Chinese-Built and Other Vessels” (United States Imposes Substantial Fees on Chinese-Built and Other Vessels | Winston & Strawn) (United States Imposes Substantial Fees on Chinese-Built and Other Vessels | Winston & Strawn)

- World Shipping Council statement (via FreightWaves) (US plans phased approach to port fees for Chinese ships – FreightWaves) and Xeneta analysis (US plans phased approach to port fees for Chinese ships – FreightWaves) on expected carrier adaptations.